Criminal laws in cold climates

Notes from a short Nordic residence

Earlier this week, I gave a paper in Uppsala University, in Sweden, on Scottish experiences with criminal law reform (this Substack is based on parts of that paper). Sweden is currently experiencing what might be termed a preventive or punitive turn in criminal law. While Sweden remains an extremely safe country, concern about issues such as shootings, explosions and criminal gangs have led to a range of initiatives including for example an inquiry into reform of criminal sentencing, proposals for anonymous witnesses, new laws on criminal forfeiture, and providing more prison places. This was a useful opportunity to consider the prominence of crime in Scottish policy-making and Scottish criminal legislation over the quarter century since the Scottish Parliament’s creation.

Crime appears to be surprisingly low among Scottish voters’ priorities. A recent Ipsos poll found that crime/law and order was the second most important issue for Swedish voters, only marginally behind healthcare (last year it came first). A Scottish Ipsos poll last year showed something very different: crime did not even make Scottish voters’ top 10 issues (from the data tables, it seems to have come in fourteenth, behind roads). That of course does not mean politicians can ignore crime: how the Scottish Government addresses issues related to criminal law will surely affect voters’ perceptions of its competence one way or another. This suggests, however - assuming voters’ views are not affected by issues such as the recent announcement of a policy of not investigating every crime - that criminal law policy overall may not be shaped as acutely by responses to public concerns as it might be elsewhere, or might have been in Scotland in the past.

The relatively low salience of crime as an issue may be in part because we have plenty of other problems to worry about. (The Norwegian criminologist Nils Christie once wrote that he preferred the crime debate in Finland to his native country, because Finland was “a country where there are still so many burning themes to disagree on that it is difficult for crime to reach the forefront”.1) The available data, however, does suggest a significant reduction in crime in Scotland over time - and one which Scots are noticing.

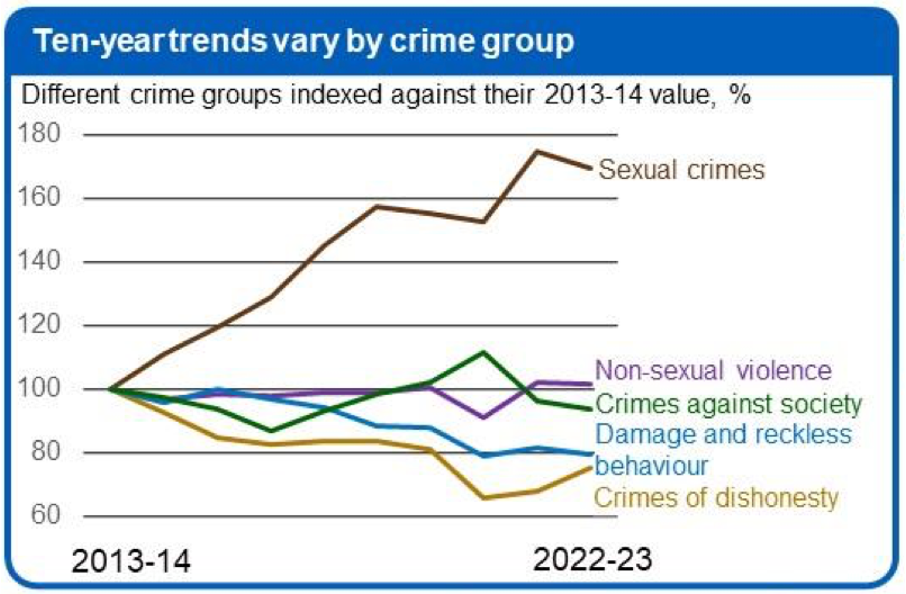

Trends in recorded crime. To start with the most serious wrongdoing, the most recent published data on homicide in Scotland, for 2022-23, reported the lowest number of cases (52) since comparable records began in 1976.2 Trends in recorded crime more generally, with one very important exception, show a flat or downward trend over the last decade:3

Although this shows recorded non-sexual violence at a relatively steady rate over the last decade, data from the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey finds that the proportion of adults reporting that they have experienced violent crime has decreased noticeably over the three most recent surveys (from 2008/09 to 2021/22):

Scots’ perception of changes in crime levels have themselves changed. Whether crime is rising or falling may have less effect on voters and politicians than what voters think is happening. Here as well, though, things have changed. While respondents in the 2021/22 Scottish Crime and Justice Survey were unlikely to think that national crime rates were falling (only 10% held that view), a majority of respondents (52%) thought that crime had stayed the same or gone down in the previous two years (38% thought it had gone up; 10% didn’t know or refused to answer). Only 20% believed crime had gone up in their local area.

That figure of 38% who believe crime has gone up nationally is an decrease from prior surveys (45% in 2019/20, 52% in 2008/09), and seems to contrast sharply with data from the 2023 Crime Survey for England and Wales, where 74% of respondents reported that crime was on the rise nationally (49% locally).4

There are two very different stories to be told about crime rates in Scotland. Sara Skott and Susan McVie noted in 2019 that homicide and non-lethal violence in Scotland has decreased significantly since the mid-2000s, with the biggest reduction resulting from a decline in the type of incidents targeted by strategies aiming to reduce gang violence and knife crime, in particular the formation of the Violence Reduction Unit in 2005. (Domestic homicide and violence decreased least.)

As the chart above on trends in recorded crime showed, however, sexual crime presents a very different picture, and one which is reflected in the work of prosecutors and the courts. The 2021 report on Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Cases (which has led to proposals currently before the Scottish Parliament including a pilot of non-jury trials in some rape cases) stated that “75% of the work of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) consists of sexual offences of one kind or another. The vast majority of High Court trials which now proceed relate to sexual offending”.5

The pattern of legislation coming before the Scottish Parliament since its inception seems in line with this data. Alongside various reforms of criminal procedure, the Scottish Parliament has passed a considerable amount of legislation concerned with sexual offences and/or domestic violence and exploitation in various forms.6 This seems hardly surprising given the trends in reported crime and court business noted above. No other types of offending have been the subject of anything remotely like the same amount of legislative activity, although something of a theme might be detected in another group of Acts aimed at improving public safety or public health.7

There is a consistent trend of expansion of the criminal law by legislation. A book by the Swedish criminologist Henrik Tham on crime and punishment in Sweden since 1965 contains a particularly striking table,8 where he classifies all Swedish legislative proposals from 1965-2021 based on whether they represent an expansion or narrowing of the criminal law (in a broad sense, so including e.g. police powers and sentencing rather than just criminal offences). In the early years of his analysis the numbers are relatively even, with the 1965-1976 social democratic government having produced slightly fewer “broadening” than “narrowing” proposals (eight against nine). A gulf gradually opens up over time and then becomes a chasm: the final section of his table (2016-2021) includes 43 “broadening” proposals and only two “narrowing” ones.

Scottish legislation lacks the neatly ordered practices of Sweden which would permit a ready numerical comparison of this sort, but a similar trend seems fairly clear. It is difficult to identify much legislation over the past quarter-century that can be said to have narrowed the criminal law, and some of the examples which exist are of mainly symbolic importance. We might point to abolishing archaic offences of sedition, leasing-making9 and blasphemy;10 raising the age of criminal responsibility from eight to twelve,11 and some early legislation designed to ensure human rights compliance in various aspects of criminal law.12 The most significant narrowing of the criminal law post-devolution came not through legislation, but the 2010 decision in Cadder v HM Advocate13 that article 6 of the ECHR required that suspects detained by the police have the right of access to a lawyer.14

The consequences of expansion can potentially be overstated. The creation of new or expanded powers and offences says little about how they will be used, while law “on the books” can wane in importance over time. We have no ready mechanism for quantifying to what extent the criminal law has substantively expanded even if it has expanded on paper.15 But while criminal law might have been seen at times in the past as something to be reined in where possible and reserved as a response to serious cases of harm done, it is now seen more as a resource which should be constantly reformed and reshaped to provide tools for addressing and ideally preventing serious social problems: a shift which the Swedish criminal lawyer Nils Jareborg once described as a move from defensive to offensive criminal law policy.16

Is Scottish criminal law becoming more punitive? It seems not, but it must be remembered that it was already very punitive. Some of the new measures under consideration in Sweden mirror tools already available to police and prosecutors here, albeit the context of their use is not always identical. We continue to have one of the highest prison populations in Western Europe, although a range of notable changes can be identified behind the headline figure (fewer people imprisoned for violent offences and carrying weapons; more people imprisoned for sexual offences; fewer short sentences but more prisoners serving longer ones).17 And if we have avoided a punitive turn in recent years, lawyers can take no credit for that, with the success of initiatives such as the Violence Reduction Unit being far more important. Crime policy will always be influenced primarily by public concerns and priorities: if overuse of the criminal law is a concern the answer is unlikely to lie in criminal law itself or legal scholarship.18

Nils Christie, A Suitable Amount of Crime (2004) 3.1.

Scottish Government, Homicide in Scotland, 2022-23 (2023).

Scottish Government, Recorded Crime in Scotland, 2022-23 (2023).

Table S27 (nb that the question here is framed by reference to the past “few” years rather than two).

Para 1.2

A quick list would include at least the Protection from Abuse (Scotland) Act 2001; Sexual Offences (Procedure and Evidence) Act 2002; Protection of Children and Prevention of Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2005; Prostitution (Public Places) (Scotland) Act 2007; Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009; Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 Part 2; Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2011; Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act 2016; Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018; Domestic Abuse (Protection) Scotland Act 2021, along with the Victims, Witnesses, and Justice Reform (Scotland) Bill currently before Parliament. The list would be even longer if it included legislation addressing female genital mutilation, forced marriage and trafficking and exploitation. I have not included these here as the drivers for bringing forward such legislation (such as international obligations) have typically been different, but they fit with a broader pattern of these areas being of particular concern to the Parliament. Various Acts aimed at improving the position of victims and witnesses, particularly vulnerable witnesses, are also relevant in this context.

This category might include the following: the Breastfeeding etc (Scotland) Act 2005; Smoking, Health and Social Care (Scotland) Act 2005; Control of Dogs (Scotland) Act 2010; Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 ss 35-37 (crossbows; knives); Air Weapons and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2015; Fireworks and Pyrotechnic Articles (Scotland) Act 2022.

Henrik Tham, Kriminalpolitik: Brott och straff i Sverige sedan 1965, 2nd edn (2022) 77-79.

Both abolished by the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 s 51.

Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021 s 16.

Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019.

Bail, Judicial Appointments (Scotland) Act 2000 s 3; Convention Rights (Compliance) (Scotland) Act 2001.

This is properly characterised as a narrowing of the criminal law, in that it restricts police powers by barring them from holding a suspect without granting that right.

James Chalmers, “‘Frenzied law making’: overcriminalization by numbers” (2014) 67 Current Legal Problems 483.

Nils Jareborg, “What kind of criminal law do we want?”, in Annika Snare (ed), Beware of Punishment (1995) 17.

I am not sure that effectively suggesting to a group of criminal lawyers they are powerless in the face of political developments is very polite, but everyone was very nice to me nonetheless.